Concussion research progresses

October 26, 2017

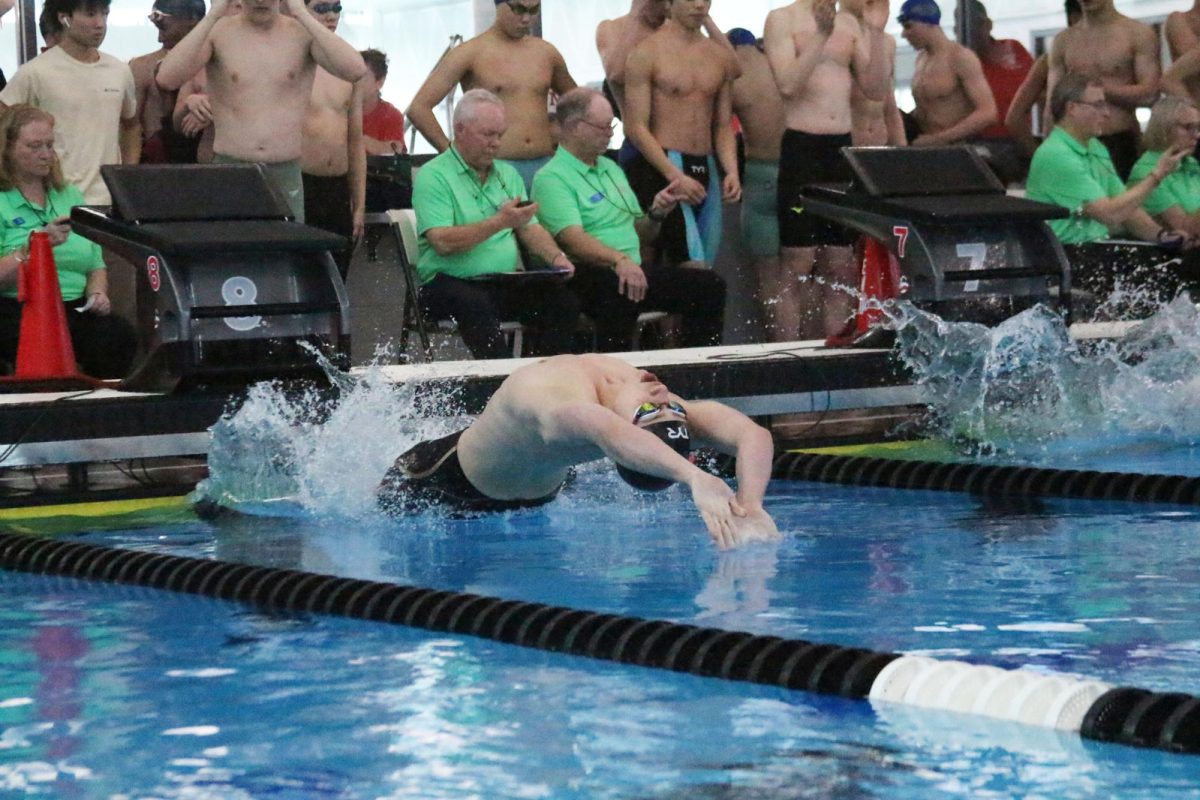

Michigan Stadium is the biggest arena in the country. Nicknamed “The Big House” it rarely goes silent. But when a head-to-head collision left Matthew Harris ‘13 unresponsive on Oct. 10, 2015 at the Northwestern vs. Michigan football game near the end of the third quarter, the stadium might as well have been empty, it was that quiet. After what felt like an eternity, he was carted off the field with his brother by his side, noticeably dazed.

“I don’t remember any of [the injury],” Harris said. “I don’t remember the hit, the play or really any part of the game. What I do remember is waking up in the trainer’s room while they were stitching up my face because there was three fractured bones in my cheek and my head was just pounding. [I had to] stay in a dark room away from my phone, computer and TV for long periods of time and [I remember] not being able to focus and concentrate. I couldn’t do any work in school. It was terrible. I think that’s the only way to describe it.”

Recent advancements in concussion research shed a newfound light on the impact concussions can have both in the short and long term. Concussions are very serious injuries of the brain that can often last weeks at a time, and have symptoms that stay for months and years to follow. CTE, or Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, is long term disease that can result from too many concussions and has become synonymous with football, especially with the National Football League (NFL).

“There is more attention to symptoms than ever before,” head athletic trainer Robert Fichter said. “Each concussion is evaluated individually so symptoms may vary. [What happens during a concussion] is that your brain is suspended inside the skull so when there is a hit or a sudden stop, the brain continues to move forward. It is the repetitive mild traumatic brain injury that leads to long term effects like CTE.”

CTE is a degenerative brain disease found in athletes, military veterans and others with a history of repetitive brain trauma, according to the Concussion Legacy Foundation. As of now, CTE can only be diagnosed postmortem, which leads to complications since there is no way of diagnosing it if someone believes they suffer from CTE. The disease has been attributed to the deaths of Mike Webster, Frank Gifford, Junior Seau and most recently, Aaron Hernandez.

“It is hard when college and high school get lumped into the research because people hear these high percentages but that is not necessarily the percentage of high school kids who are stricken with this disease,” athletic director John Grundke said. “That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be worried about it but the research can be deceiving.”

Although the worry regarding concussions has been amplified in the past five to 10 years, LT and its fellow West Suburban Conference (WSC) schools have been proactive regarding the prevention, treatment and information each school and athletic program has regarding concussions, Grundke said.

“We come together [for WSC athletic director meetings] each month and share information,” Grundke said. “We do a lot to figure out what’s best for our kids. LT was focusing on concussions even 13 years ago when I got here. The football team doesn’t dress in full pads and practice in full pads everyday but it is not just for concussions, but also wear and tear on their bodies all together. There are new restrictions placed on schools to help control injuries, but it doesn’t affect what we do here because we were already doing those things to be proactive and keep our players safe. Although every once in awhile we’ll see a spike in the numbers of concussions which starts the conversation as to why it is happening and we will try to find answers and keep the conversation ongoing.”

Concussions are all relative, so what may be the main symptom to one person may not even be a symptom to another, Fichter said.

“Concussions are completely different for everyone,” Harris said. “Even if someone gets one, that’s too many. You have to analyze for yourself individually when you do get them. You cannot compare yourself to others and think you can keep on going because you have less than another person.”

The widespread research and resultant skepticism has resulted in a decrease in football players in the Chicagoland area and nationally. Whitney Young High School could not field a varsity team and multiple freshman B games were cancelled during the 2017 season due to a lack of a team to play.

“Typically we have been able to field a full freshman B team and have a complete schedule,” Grundke said. “This year we had to find around five games because of those nine teams we usually play, five of them were unable to field a freshman B team. We’ve had fluctuating numbers in the past so it’s unknown as to if it is just one year, or if it will decrease consistently, which could be due to concussion worry.”

Football is not the only sport that sees concussion injuries. Across the board the numbers stay relatively consistent when soccer, hockey and other contact sports are looked at too, Fichter said.

“I support the decision of a parent to let their kid make the decision as to if they want to play football or not,” Harris said. “I hope kids recognize and learn how violent and truly dangerous the game is but at the same time the game brought so much joy, passion and characteristics into my life that I wouldn’t deny that to anyone because that is a personal decision that everyone should make for themselves.”

Harris chose to retire from football during his 2016 senior season at Northwestern University when he suffered what he decided would be his last concussion. He had hoped to enter in the 2017 NFL Combine and later be considered for the Draft.

“I don’t know if I will ever be able to get to the same spot I was before [football] but now that I’ve been away from the game for a little while my memory has been getting better and I can concentrate more,” Harris said. “After that Michigan game I told myself I’d give it one more round, [because] with concussions you don’t know what the symptoms will be like in the long run.”

![Movie poster for '[Rec]" (2007).](https://www.lionnewspaper.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/rec-640x900.jpg)