Book banning increases in Illinois

LT policies in place despite past curriculum parent objections

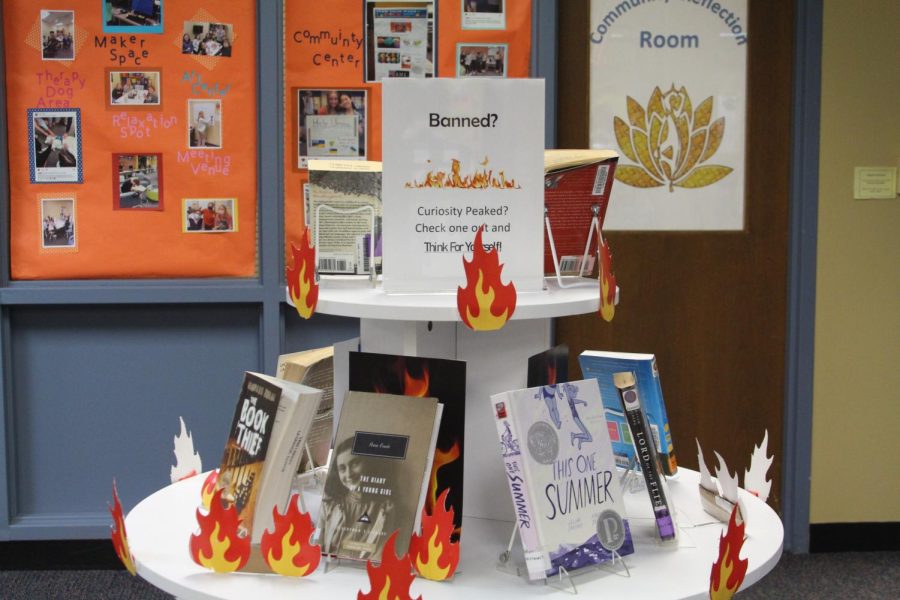

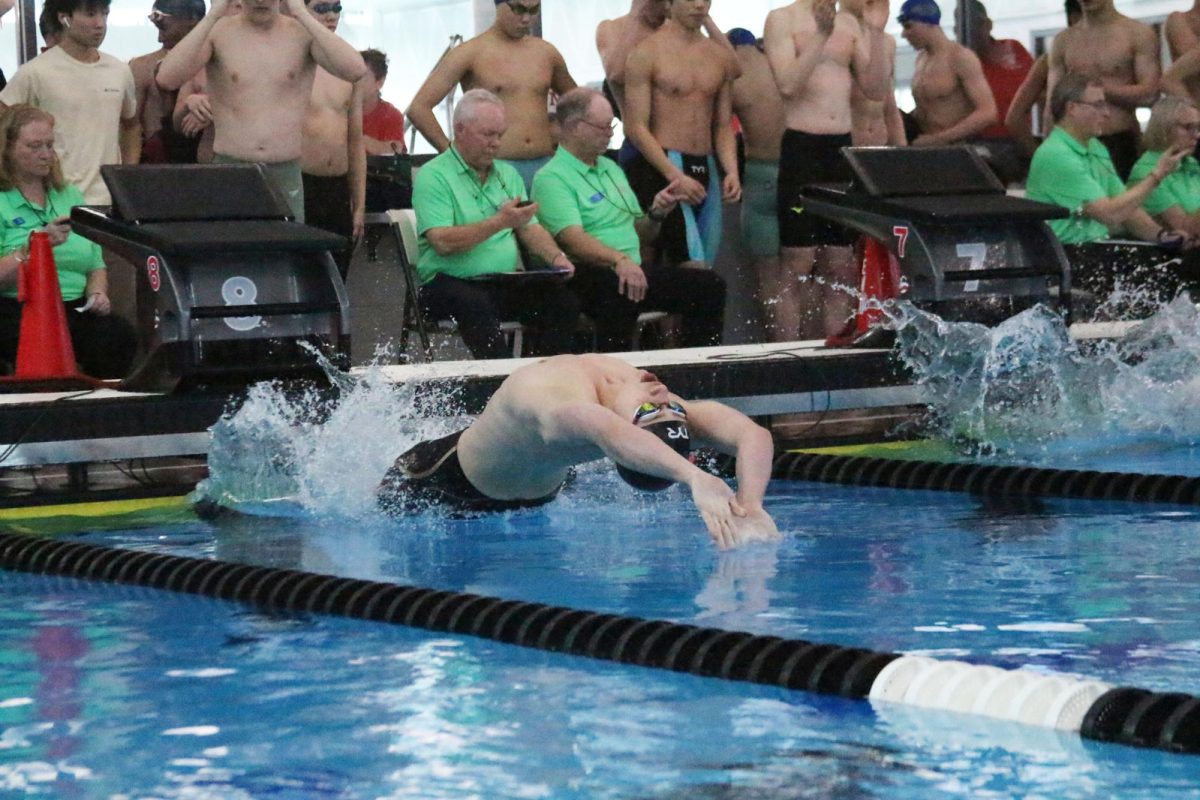

A display of banned books as spotlighted in the NC library for students, featuring titles such as Anne Frank’s “The Diary of a Young Girl” and Mariko Tamaki’s “This One Summer.” (Mardegan/LION)

November 7, 2022

As the 2022-2023 school year begins, a surge in book banning has increased, specifically with LGBTQ+ literature, in Illinois schools, according to a WCBU.org article: “Book challenges and bans surge nationwide, and Illinois is no different.” While LT hasn’t faced any literary objections this year, it’s something that’s been attempted in the past.

“I think that the desire to keep kids from reading comes from a faulty understanding that when you read something like a gay character, for example, it’ll make you gay,” English teacher Nicole Lombardi said. “Some people really believe that.”

The act of book banning isn’t anything new. It’s an unfortunate tactic used by people trying to control an environment by placing their beliefs onto others and shuttering ideas that go against it, NC librarian Cheri Price said. In having a significant input in what books are offered in the library, Price values having a wide selection available for students.

“The American Library Association has a ‘Bill of Rights’ and offering materials that offer a wide range of views should be represented, otherwise it’s censorship,” Price said. “In a school, you have to censor a little bit, but [offering a variety of books] is a part of the principles of librarianship.”

When Price joined the LT faculty 10 years ago, she created a Collection Development Policy, which is a 14-page manual that offers the school’s library mission statement, including information on how books are chosen as well as how fines are handled, among other things, she said. Within the manual, it also states how a person could challenge a book within the school and the form they must fill out to do so.

The library isn’t the only place in school with a policy in place for the instance that a book gets challenged. It’s instruction for English teachers to put a statement in their syllabus that if a parent objects to any assigned literature, they must notify their child’s teacher at least 10 days prior to the start of the unit, Lombardi said. Being that junior year, Advanced Placement (AP) English classes cover Toni Morrison’s “Beloved,” a novel frequently found on banned book lists, Lombardi has experience with parents who elect to have a student opt out of a unit study.

“[If an assigned book is objected], the teacher is required to offer an alternative unit [for the child] completely individualized,” Lombardi said. “[In a past case with a student], I came up with some alternatives and she didn’t like them. She was in a self-study. She missed out on so many lessons and discussions with ‘Beloved.’”

Lombardi is passionate about the topic of books being banned, and even found herself in a group discussing the topic, she said. Attending an event in association with the Forest Park Public Library, she met with other writers at a local business, where they planned to discuss the prompt for an essay contest the library was hosting in regard to what literature meant to them. It was then when it landed on an older gentleman that the group realized not everyone shared the same opinions.

“The more and more he talked, the more we realized, ‘OK, he’s someone who supports book banning,’” Lombardi said. “It was super tense.”

Highlighting books that represent people from different cultures and backgrounds is important to help today’s youth become future world citizens, Lombardi said.

“The more that young readers see themselves in characters, the more they connect to the story,” Lombardi said. “It’s easier to envision yourself overcoming obstacles that literature [puts] forward if that [character] comes from your culture. We do our whole future a disservice by not introducing children when they are young to the stories of people everywhere.”

![Movie poster for '[Rec]" (2007).](https://www.lionnewspaper.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/rec-640x900.jpg)