Center for Independence march

Assembling at train station in DTLG, protesters implore commuters to encourage hiring disabled people

December 6, 2016

Protesting the disparities in employment for people with disabilities, protestors with The Center for Independence Through Conductive Education came together at the train station in downtown La Grange on Nov. 16 to raise aware for their cause, Center employees said.

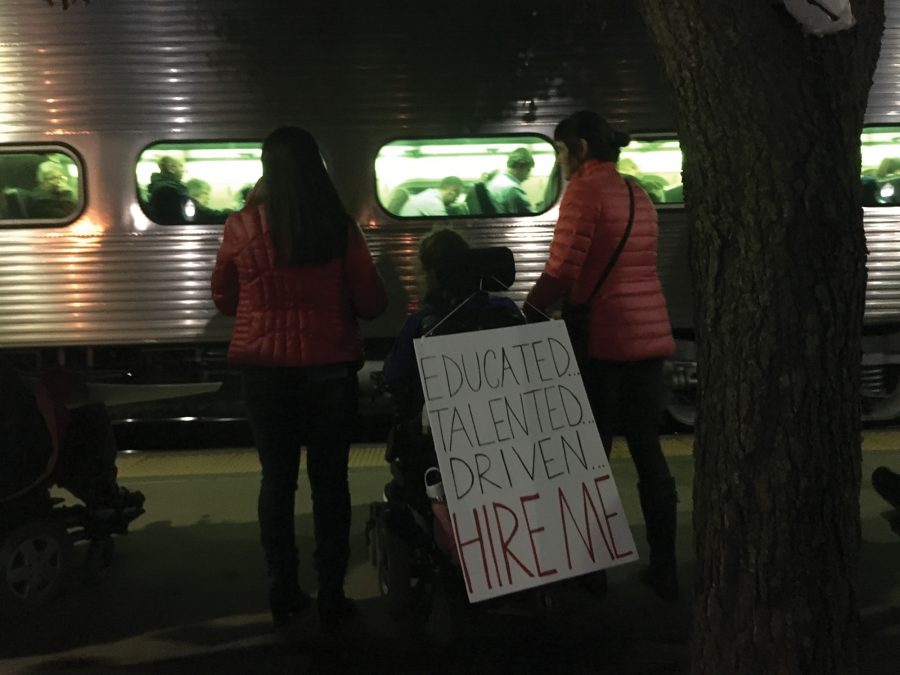

Lining the platform, 16 people—five of whom took the line in their wheelchairs—passed out brochures, and donned signs expressing the need for hiring more people with disabilities, which blew in the wind as the trains flew by the protesters at high speeds.

Signs asking commuters whether they are “on your way to work?” adding that people with disabilities “should be too!” while another implored businesses to hire the disabled because they too are “Educated… talented… driven.” Another sign informed passersby about how “70 percent of people with disabilities are un/underemployed.”

The unemployment rate for people with disabilities is actually not 70 percent, but 10 percent—which accounts those who are actively seeking employment, not those who have given up—The U.S. Department of Labor’s website claims. However, the labor participation rate for those with disabilities, which includes those who aren’t actively seeking a jobs, is lagging behind at only 20 percent having employment, compared to the 68 percent labor participation rate for able-bodied individuals.

While nearly a 48 percent discrepancy between those with and without disabilities, the government provides some sort of assistance to many disabled people who aren’t apart of the 20 percent of disabled people with jobs. But the organizers of the protest said that some disabled people don’t want to rely on the government assistance and have ambition and drive too.

One of the organizers, Ani Hunt, 27, said that she thinks that the group’s protest “gets the point across,” and that they are bringing awareness to an issue that is frequently neglected, Hunt said.

“I feel like people are staring at us, like they don’t know what we are doing, but I think it has been pretty powerful so far,” Hunt said as the protesters waited for the next train to arrive to begin marching again. The protesters stood waiting, conversing during the long periods when there was an absence of trains. “I mean, it’s pretty small scale, but any awareness is significant.”

Hunt, who has Cerebral Palsy, studied at the University of Chicago in Urban Campaign and claims to have faced discrimination while seeking an internship to finish her graduate degree in social work. She eventually got an internship with The Center, where she is set to work as a social worker once her degree is complete.

“When I was trying to get an internship to finish my graduate degree in social work, I personally experienced resistance to being considered for an internships,” Hunt said. “Of course, no one can outright say we aren’t hiring you because of your disability. But it’s a lot to take on, and people have to be willing to see you and your disability as an asset.”

The American’s with Disabilities Act makes not hiring someone based upon their disability illegal, but it’s a difficult law to enforce, David Levin, an employment attorney with the office of Tod Friedman, said.

“I think that the discrepancy [in employment for disabled people] is in the enforcement of it,” Levin said. “Certainly, it’s a very strongly worded law and well worded I think on paper, but I think obviously there still is a significant problem with [disabled] people finding jobs.”

In most cases, proving that discrimination—whether it be a disability, a person’s gender, or sexual orientation—took place is difficult because “it’s never really all that clear,” Levin said, making their job as an attorney much more difficult.

“I firmly believe that most employers that are discriminating against employees or prospective employees because of disabilities or any other wide range of reasons, they are not openly blatant about it because they know what they are doing is wrong,” Levin said. “It can be difficult sometimes to prove discrimination in what we call a failure to hire case, because they can really come up with any other reason to why they didn’t hire a person.”

The Equal Opportunity Commision, the U.S. agency that handles the enforcement of discrimination claims related to the A.D.A., was not able to make a spokesperson available for this story.

But the protesters in La Grange passed out nearly all of the 60 brochures they printed out for the march. The consensus among the protestors was most positive, with the protesters saying that they thought their march went pretty well.

“I thought it was good,” said Kacie Herbst, development assistant at the Center and an organizer of the protest. Reflecting over dinner at Noodles and Company, Herbst admitted that they could’ve made a larger impact if they had done more preparation, particularly in checking the schedule for the trains. But Herbst said that they still have intentions to do more things like this in the future.

“We definitely want to do it again, that was something we really took away from this afterwards,” she said.

In future protests, Herbst said, they would work to have more one-on-one interaction than the march at the train station produced. Whether it be marching down La Grange Road or reverting to their original intention of taking the protest to Chicago’s Union Station, Herbst said that this won’t be the last.

Whatever they do in the future, the protestors called it a day a 5:17 p.m., almost an hour after they first started protesting. Afterwards, they all embarked to Noodles and Company for a celebratory meal.

Plastered on the see-through door of the restaurant, the protestors were greeted by a “now hiring” sign. Walking through the door, one of the protestors took the time to laugh. “Ironic,” they said as they got in line and celebrated.

![Movie poster for '[Rec]" (2007).](https://www.lionnewspaper.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/rec-640x900.jpg)